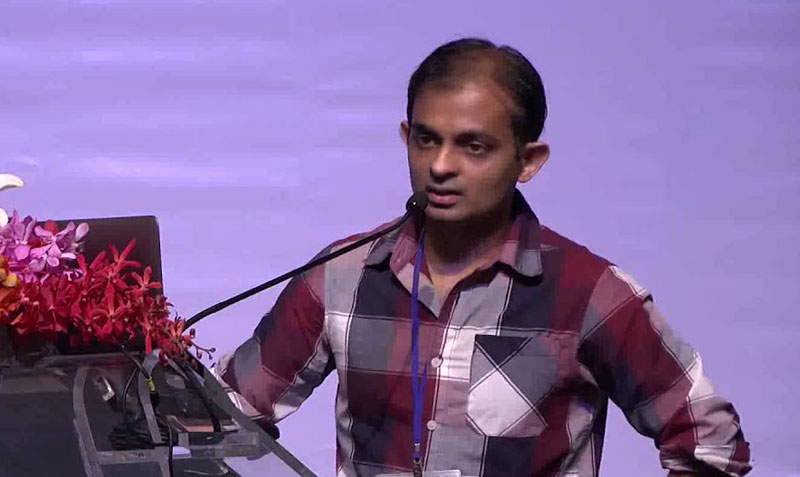

Have MOOCs Become Something People Love to Hate? Class-Central’s Dhawal Shah in Conversation

By Henry Kronk | IBL News

In the fall semester of 2011, Stanford University Professors Sebastien Thrun and Peter Norvig launched one of the first of a new generation of massive open online courses (MOOCs) on artificial intelligence. Dhawal Shah signed up for his course. Within that fall semester, more and more MOOCs were launched. An aspiring developer, Shah built and launched a site to track and catalog these courses. Ever since Class-Central.com has provided a map to the MOOC-iverse. IBL News reached out to Shah the ongoing evolution of MOOCs, and the occasionally negative reputation they have garnered.

Henry Kronk: Many publications have declared recently that MOOCs have failed to live up to their promise. Many of these authors don’t mention what MOOCs promised them in the first place, but if we can look beyond that and view this issue from 10,000 feet, do you think their characterization is fair?

Dhawal Shah: I was part of the first-ever cohort of MOOCs back in 2011. I did the AI class from Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig. This was the first one before they were called MOOCs and before there was Coursera or Udacity. They were just called Stanford Online Courses. For me, personally, the part of the experience was the community. Any question I had, somebody had already asked it and it had been answered. Another draw was access to high-quality education.

One of those has expanded. There are more courses than ever in 2018. There are almost 12,000 MOOCs from 900 universities. But the community itself isn’t thriving. The community has split into multiple smaller cohorts. That’s why you don’t get the same feeling that I had back in 2011.

In that case, I feel MOOCs haven’t lived up to my expectations of what I hoped they would be. But when the thought pieces come out, they usually talk about the completion rates and other barometers which I don’t think are very important. You set up the expectations to fail if the definition of success is completion rates. With any online activity where people aren’t invested—it doesn’t matter if it’s online courses—completion rates will be low. It’s the same even with books. I have so many books that I own, but I haven’t read most of them. That doesn’t mean that books are failures.

Henry Kronk: Let’s talk more about completion rates because that’s been a known phenomenon—that MOOCs have low completion rates—since really early in their lifetime. This obviously varies depending on the platform and the individual course, but MOOCs still have a completion rate—one might be lucky to get above 10%.

In their January issue, Science Magazine published an article by MIT researchers Justin Reich and Jose Ruiperez-Valiente titled “MOOC Pivot: From Teaching the World to Online Professional Degrees.” In the article, the authors describe some familiar arguments against MOOCs, one of which is the low retention rates they have maintained. Now the authors describe these low retention rates as both the “bane of MOOCs” and as a “bugaboo.” How would you characterize low-retention rates in MOOCs?

Dhawal Shah: Regarding the study, I don’t think the authors analyzed the business decisions that MOOC providers and universities have taken. If you look at their numbers, you see that in 2015-16, there’s a sudden drop in retention and course completions. And that’s probably because, at that time, Coursera and edX stopped offering free certificates. That reduced retention, that reduced completion, was because the reward wasn’t there. They failed to look at that.

Also to put the article in context, out of the 900 universities that offer MOOCs, they only looked at two institutions [MIT and Harvard] that offered about 250 out of the 11,000 available courses. So the retention rates were only those of MIT and Harvard courses. When the free certificate went away, these courses went down in value.

There are so many other options available. If you don’t want to do a course that offers a certificate, you can choose one from other universities, not just MIT or Harvard. So I think that analysis failed to look at the business decisions of the providers and the universities.

I also think that nowadays, providers are more focused on the users who are paying. When it comes to paying users, the completion rate is pretty high.

For free users, they might choose to sample a few classes and then they finish only one. Most learners have limited time. So if someone tries out five courses and completes one, their completion rate is 20%. It doesn’t accurately convey my participation.

I still think completion rates are low, but if you set that up as a metric of success, then anything online that is free and open will fail.

Henry Kronk: We don’t talk about completion rates of YouTube videos. We don’t talk about completion rates of podcasts, or completion rates of Facebook messages, etc. Why do you think this metric has been such a sticky point of contention when it comes to MOOCs.

Dhawal Shah: The only reason we talk about completion rates with MOOCs is because we know about them. If you think about companies like lynda.com or Pluralsight, these companies have been around a lot longer, but we don’t know anything about them. You don’t know any metrics. You don’t know how many people are taking them, you don’t know how many people finish them. I think we should appreciate the fact that, because it’s universities who are running these courses and willing to share that data, we know about it. That’s probably the reason they get hammered more. It’s a stat that we know.

When I write things on Medium, it tells me how many people have read it. But it doesn’t tell me how many people have finished it. I don’t think completion rates accurately captures the impact or the value of the article.

Henry Kronk: Ok, so let’s move on to another point that the MIT authors make. And, like you already said, this only applies to their sample, which looked at just courses offered by Harvard and MIT, so it’s already limited in that respect. They make the point that most of the learners the MOOCs serve are based in “affluent countries or affluent communities.” Is this something that is widespread, in your experience, throughout MOOCs in general, and, if yes, is that a source of concern?

Dhawal Shah: First of all, the MOOC providers are businesses, so I don’t think there’s any reason for them to look beyond affluent countries to recoup their costs. $50 in the U.S. is very different from $50 in India or other developing countries, so I think that matters.

I think just launching a website and building up some technology, you won’t magically reach people in other countries.

We should also look at the topic of subject matter. I grew up in India and studied in India. There’s no way that I would have taken 90% of the courses offered at MIT or Harvard, especially in the humanities. I would have loved to do a course taught by David Malan in CS, which is more practical. That’s something we need to take into context.

One interesting fact that I recently learned is 800 students graduate every week from Dr. Chuck’s Python Specialization on Coursera. Around 20% are from India. So I think in that case, the penetration in other countries is much higher. But if you aggregate numbers across the board, it does not reflect an accurate picture of MOOCs. There is still a lot of work to be done. But as the paywalls continue to go up, it will become more difficult to reach people in other countries.

There’s also a whole set of local platforms coming up that offer courses in local languages. MOOCs are mostly for an English speaking audience and, to some extent, Spanish speaking. If you want to reach more people in non-affluent countries, there’s still much more work that needs to be done. But I’m not sure there are any financial rewards to achieve that. The price of these countries is too high.

Henry Kronk: What you’re saying is, for this to be a global education initiative, MOOCs will need to maintain a base in communities who are willing to pay for not only certificates but also to clear paywalls.

Dhawal Shah: Yes. And also, MOOCs need to be free to break into some countries.

Henry Kronk: I began by talking about the negative coverage of MOOCs in the past year or so. I want to return and even zoom out of further. Forbes’ Derek Newton even compared credentialing and micro degrees as a “Bait-and-Switch” tactic last November. Why do you think MOOCs are all of a sudden a subject people love to hate?

Dhawal Shah: I think the original media coverage and hype in 2011 and 2012 made for a very adversarial environment. Some of the founders also made huge claims. I think Sebastian Thrun predicted that, in the future, the world would only have 10 universities. That got more attention than what other founders were saying. That created a ‘Us vs. Them’ mentality. It implied that only one would survive.

So whenever people have the opportunity, they write about MOOCs’ negative aspects because of this relationship that was created. But other providers were more measured. Coursera, edX, FutureLearn—from the beginning, they always saw themselves as partners with universities.

Henry Kronk: This question could also benefit from a much deeper discussion about the media, but, for my last question, I wanted to switch gears again and talk about the role MOOC providers among universities and with online courses. In the U.S., there’s been a trend recently where for-profit colleges and universities have begun transitioning and spinning their institutions off as non-profits while maintaining the original company as an online program manager (OPM). There’s also a checkered past in the U.S. with for-profit universities that has been going on at least since the passage of the G.I. Bill after World War II. American for-profits have in the past been found to misrepresent their programs and defraud their students.

In my opinion, OPMs are some of the most mercurial entities operating in edtech right now. They might provide simply the digital infrastructure to bring a course online. But they also might take care of advertising, recruitment, marketing, and all these roles that for-profits have previously come under fire for. With the mandate to exceed the bottom line, do you think that there’s any danger that MOOC providers will one day become the for-profit colleges of the previous decade?

Dhawal Shah: They have in some cases been aggressive about monetization. They sometimes aggressively change policies. But they also still work with traditional universities, and I think that’s the big difference between this world and the old world.

I don’t know of any for-profit college that’s launching degrees on these platforms. I actually think that providers don’t want that. They are much more exclusive. A lot of the smaller universities can’t even offer courses on edX or Coursera. They are very selective and they’re very concerned about their brand. At least for the next few years, I don’t think what you described will be possible.

But also the amount of money put into these courses does bring pressure to monetize. That has led to taking away the free component from MOOCs and slowly raising the paywall. Udacity has increased prices steadily over the past year, year and a half. They used to offer $200/month and if you finish a micro degree at their college, you get half the money back. That was the early model. Now the model is, for a four-month program, you pay $800-$1000 and there’s no money-back guarantee. If you don’t finish in the allotted time, you lose access to the content. If you want to finish it, you basically have to pay $1,000 and sign up again.

So there is some aggressive monetization happening on different platforms. And sometimes people do get caught unaware. But overall, these companies do have much higher aspirations. They don’t just want to make good revenue. They want to be global brands. The universities also will likely put some pressure and hold them back.

For regular updates on the MOOC space, check out Shah’s MOOC Watch, which he updates regularly.

En Español

En Español